Would an Islamist Syria be Worse than a Weak Assad?

fter years of a stalemate in which the Russia- and Iran-backed regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad had the upper hand, Turkey-backed and Al Qaeda-linked Sunni groups such as Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham swept through Aleppo, once Syria’s largest city, and pushed south.

The collapse of the Syrian Army was stunning and may be quicker even than at the beginning of the Syrian civil war in 2011. The Syrian Army reportedly abandoned Hama to establish defensive positions near Homs, a city that occupies the crossroads that not only connects Aleppo to Damascus in the south, but also controls the major route eastward. Rumors spread through Damascus that a coup was underway that could end the Assads’ more than half-century rule.

Within the West, there is giddiness. Washington may rue Assad’s downfall.

[Assad] did the Islamic Republic of Iran’s dirty work in exchange for their help crushing the Syrian people’s aspirations for something better.

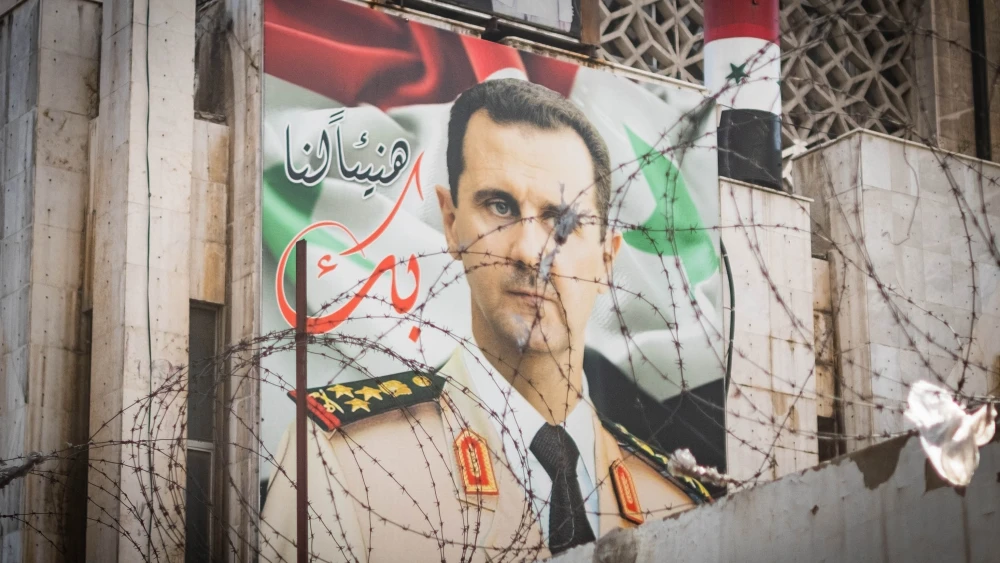

Make no mistake: Assad is odious. He colluded with North Korea on a secret program to get a nuclear weapon, an effort that failed only because Israeli aircraft destroyed the al-Kibar plutonium processing plant near Deir ez-Zour on September 6, 2007. While he fights Sunni Islamists now, he transformed Syria into an underground railroad for suicide terrorists seeking to attack American forces in Iraq and Iraq’s new government. After the Syrian uprising began, the “Western educated eye doctor” then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and former Senator John Kerry were so anxious to engage showed his true colors: He used chemical weapons against his own population. He facilitated Hezbollah and did the Islamic Republic of Iran’s dirty work in exchange for their help crushing the Syrian people’s aspirations for something better. “Caesar,” a Syrian military policeman, defected with tens of thousands of photographs depicting systematic torture.

As Daniel Pipes noted in 2013, “Mr. Assad’s survival benefits Tehran, the region’s most dangerous regime. However, a rebel victory would hugely boost the increasingly rogue Turkish government while empowering jihadis, and replace the Assad government with triumphant, inflamed Islamists.” The late Senator John McCain may have been correct that Syrian moderates had the upper hand when the Syrian revolution erupted but for too long, he ignored their Turkey-fueled radical transformation after President Barack Obama failed to throw them support.

Today, the difference between Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham and Al Qaeda is minimal. This is one of the reasons that Syrian Democratic Forces, the largely Kurdish militia that backs the Kurdish-run Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), rushed forces to Aleppo to protect the city’s Christians, Kurds, and Yezidis from slaughter.

Deferring the post-Assad vacuum to Turkey could be a generational mistake.

The choice policymakers must consider is not a strong Assad versus a pluralistic, democratic opposition, or a strong Assad versus a weak Islamist regime; rather, it is a weak Assad ensconced in Damascus or Alawite strongholds along the Mediterranean coast versus an increasingly strong, radical Sunni regime with the worldview of Hamas, if not the Islamic State, but with the full and open backing of Turkey. In such a scenario, Turkey is not analogous to Qatar, its Islamist ally and sometimes-financier, but rather to Iran. After all, Turkey, like Iran, invests in an indigenous and increasingly lethal weapons program that it exports to proxies beyond its borders.

Assad must go, but how others fill the vacuum left behind matters. Few will shed tears if Assad flees to Iran, Russia, or hangs from a Damascus streetlamp, but deferring the post-Assad vacuum to Turkey could be a generational mistake that will endanger the United States, Israel, Jordan, and the broader Middle East. It could, in essence, snatch defeat from the jaws of victory, simply swapping out sponsors rather than decoupling Syria from terrorism.